Sync

Write the test first

func TestCounter(t *testing.T) {

t.Run("incrementing the counter 3 times leaves it at 3", func(t *testing.T) {

counter := Counter{}

counter.Inc()

counter.Inc()

counter.Inc()

if counter.Value() != 3 {

t.Errorf("got %d, want %d", counter.Value(), 3)

}

})

}Try to run the test

Write the minimal amount of code for the test to run and check the failing test output

Write enough code to make it pass

Refactor

Next steps

Write the test first

Try to run the test

Write enough code to make it pass

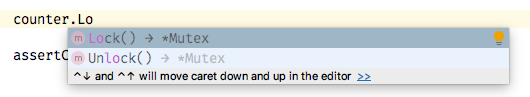

I've seen other examples where the sync.Mutex is embedded into the struct.

sync.Mutex is embedded into the struct.

Copying mutexes

Wrapping up

When to use locks over channels and goroutines?

go vet

Don't use embedding because it's convenient

Last updated